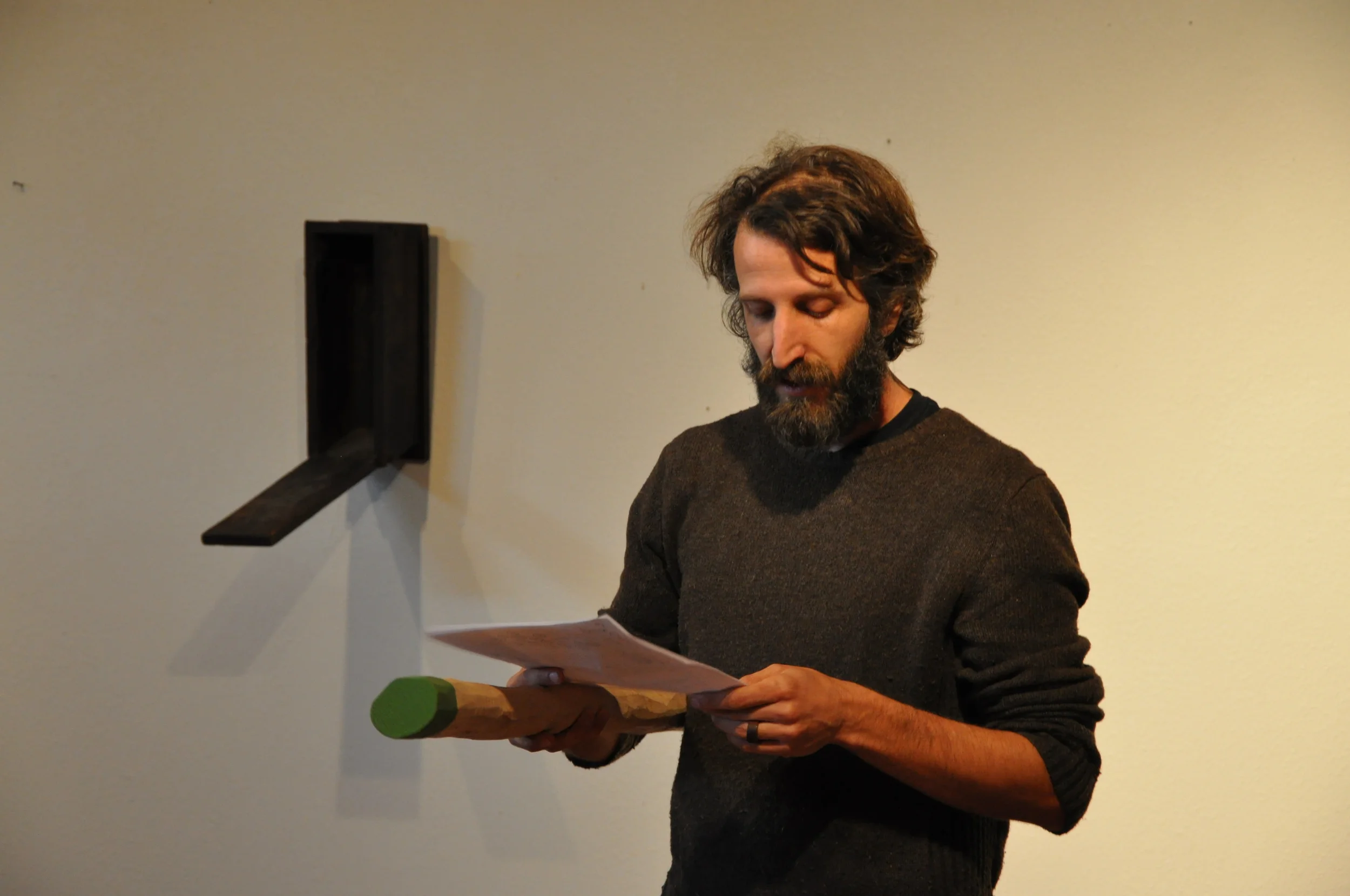

Michael Swaine, Dead Reckoning, BAY AREA NOW 7, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, 2014

1-the shape of things THAT FLOAT IN WATER

AMBERGRIS. THIS WONDERFUL WORD THAT FOR HUNDREDS OF YEARS WAS USED TO DESCRIBE THIS SOLID WAXY FLAMMABLE MATERIAL THAT WAS FOUND FLOATING IN THE SEA A WAY TO DISTINGUISH IT FROM THE OTHER AMBER. THIS WORD CAN BE PRONOUNCED TWO WAYS AMBER GREASE OR AMBER GRIS

LETS TRY BOTH TOGETHER LIKE A CHOIR ALL TOGETHER

FIRST AMBER GREASE

- ALL TOGETHER...AMBER GREASE

NOW... THE OTHER WAY OF SAYING IT

ALL TOGETHER… AMBER GRIS

THIS IS MORE VALUABLE THAN GOLD. : SOMETIMES A PALE YELLOW IN RARE CASES A DARK BLACK, THIS OCCURS WHEN THE LARGE WHALE SWALLOWS A SQUID. OHH FOR THOSE WHO MIGHT NOT KNOW AMBERGRIS IS WHEN A SPERM WHALE VOMITS UP A MYSTERIOUS MIXTURE THAT IS USED IN THE MOST EXPENSIVE PERFUMES. ITS SMELL HAS BEEN DESCRIBED AS ENTRANCING TO 9 OUT OF 10. AFTER THE FECAL SMELL FADES TO A SWEET EARTHY…

2- almost touching sculpture

(before I GET TO THE zipper)

most people when in museums

touch things they are not suppose to

when the guard isn’t looking

(ask guard to look away)

everyone raise your hand if you have touched nathan’s sculptures

don’t worry the guards aren’t looking

and now raise your hand if you have touched something ELSE in a museum that you shouldn’t have

ok put your hands down

ok tell guards they can look now

NEXT…..

(TELL GUARDS THAT WILL ABOUT TO HAPPEN IS VERY SAFE AND WE DO HAVE PERMISSION, ASK CURATOR TO NOD MAYBE EVEN WAVE

_______________GET NAME OF CURATOR_________)

----------GET NAME OF GUARDS______________)

i want you to all point your finger as if about to touch

it get close

BUT don’t’ touch it then

before you do it as you get close WE WILL HAVE TO ALL CIRCLE AROUND THE SCULPTURE...SPREAD OUT

NOW ...REACH AS IF YOU ARE ASKING FOR A DANCE, BUT YOU ARE ABOUT A FOOT AWAY

NOW MAYBE REACH AS IF THEY ARE IN THE WATER AND YOU WILL HELP THEM OUT...CLOSER

6 INCHES

NOW CLOSER TO THE TOUCH

3”

2”

1”

½ “

1/4”

1/8”

1/16”

1/32”

OK NOW THE DISTANCE OF A HUMAN HAIR AWAY FROM THE SCULPTURE

REALLY TRY TO JUST BE AS CLOSE AS POSSIBLE WITH OUT THE TOUCH

NOW HOLD HERE

just get very close… hold

AGAIN, WE ARE NOT GOING TO TOUCH THE SCULPTURE

WE WAIT WE WAIT

AND NOW WE BACK UP

3- GERMS ARE EVERYWHERE

now, I will remind you of all of the people

who go to the bathroom but don’t wash their hands

I HAVE READ THE STATISTICS - I DON'T WANT TO TELL YOU THE NUMBERS I FOUND… IT HAPPENS HERE ALSO

1000 of people walk by and they all sneak a small touch. OF A SCULPTURE… goose THAT IS goose to poke

THE GUARDS CAN’T CATCH EVERYTHING

IT IS UNFAIR TO EXPECT THEM TO STOP EVERYTHING

4- toilets in museums, and how often they have been peed in

{17 FOUNTAINS, MARCEL DUCHAMP-

one peed in BY PIERRE PINONCELLI }

5- when we are in a bathroom -how do we space ourselves

nathan (not this nathan but a different nathan) asked me “does size matter?”

i paused because

i thought he said “was eyes sadder”

i looked close to his eyes to see if he was crying

i gazed into his eyes

he looked into my eyes

i waited

i looked

and i looked

waited

{pause}

lets pair up with someone you did not come here with

look into their eyes- your new partner

“was eyes sadder”

so look for the tear

wait for it to come

eye to eye

look at the color and imagine the water

the deep deep water

flowing forward

wait

ok now raise your hand if you see the water

the welling up

it doesn’t have to be a tear just the water behind the dam

the surplus

put both hands in air

like a stretch towards the clouds above

6- zippers wrtting in the snow

bring yellow zipper

i unzipped my pants and nathan unzipped his pants

and we compare

i asked if he knew how to write his name

he said that he never grew up with enough snow

I SAID THAT I WAS BORN IN BUFFALO MANY MONTHS OF PRACTICE

I TELL HIM I CAN SHOW YOU

i ASK IF I CAN hold on to his…...IT WILL MAKE IT IS EASIER FOR ME TO SHOW HOW EASY CURSIVE IS AND HOW TO DOT EYES

HE REMINDS ME ABOUT THE LACK OF SNOW

AND I SAY THAT THIS FLOOR WILL BE FINE

Hazel White, BAY AREA NOW 7, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, 2014

Sonnet to Dead Reckoning

1.

Once upon a time, “Let’s suppose it is 3,000 years ago and you have transported yourself into a fisherman’s boat, far from land,” John Edward Huth begins his book, The Lost Art of Finding Our Way. The fisherman, I want to place her in a spinning yellow donut “sings to himself as he hauls in a net from the sea. . . . “You ask him, ‘Why is it warm in the summer and cold in the winter?’ His outstretched arm traces an arc toward the sky, and he says that the Sun takes a high path in the summer, and the days are long; but in the winter the Sun has a low path, and the days are short. His voice has no hint of uncertainty.”

2.

Here I am, at my point of departure. I am a poet, so I’ve written a sonnet, 14 lines of thought, composed over the last 14 days in reference to time and place and the title of Nathan’s sculptures, Dead Reckoning. Nathan begins, he says, by rolling “out the clay into 3/4" thick slabs, like floppy sections of plywood or heavy thick fabric.” As a poet navigator, I’m beginning with a structure of 14 lines, which feels sturdier than aiming for a distant and invisible point on an empty plane. Like a sailor, I’m heading into the wind on my way out, during the first 8 lines, in the hopes of all of us enjoying an easy return.

3.

Setting off, one wants a cheerful adventure tale and praise. And yet each point of departure is pegged on a grid of past experience. And I am freshly arrived from a site project that is in part about the military. August 7, Museum of Craft and Design, 3 miles south of here, Ehren Tool a large man, a potter now but a Marine during Desert Storm, takes the mic and explains the only statement he is comfortable saying is “I make cups.” Each cup, nearly 15,000 of them now, tells the story of a veteran, is a gift to the veteran, with Ehren’s wish that it facilitate communication in the veteran’s family or community. He doesn’t like the mic. He ventures that he wishes he could do more than make cups. What’s unspeakable floods the room; language founders in the distance between his military service in the First Gulf War and our understanding. The water begins to rise, and a woman in the audience searching for an oar questions him about the accumulation of horror he hears in the stories—and his voice breaks.

4.

Peril: A loss, an absence of shape, a change of weather. I do not know the sea, but I have read that there are tripping buoys, wreck buoys, tsunami buoys, and military buoys that release light and smoke. I have seen a map that puts the waterline sometime this century at Folsom and 5th, a couple of blocks from here. We do not know what this area will look like then. The evolutionary interactions among natural processes are so complex, it’s impossible to predict which species will be here, which habitats will have gone.

5.

We are all navigators. Place and language provide the syntax of our movement. “Go is what we have,” writes poet Bhanu Kapil. On land, we move forward toward light. We have a preference for high places, to gain a large perspective and see what’s advancing toward us, and we seek shelter. As we travel, we are encouraged by any sense of plenty—flocks of birds, reflections of sky on freshwater, news of environmental and social justice, and signs created by people who have walked before us: piles of stones, say, or donuts and pillows or a ladder rising into the air. We long to be always upright. We dread a flat continuous horizontal with no signs of life or habitation.

6.

Dead reckoning has an inherent percentage of error, which grows larger as time goes by. Like everyone else, I’m spinning all through this sonnet time in news breaking on the Internet from Gaza and Ferguson. I’m in a worry of direction. Research shows a lost person proceeds randomly, first in a straight line this way, then suddenly changes direction and later turns again randomly. Eventually, as search and rescue teams know, we are likely to spiral and show up back close to where we began.

7.

My first reading in a museum space was just across the street, in 2008, a month before the presidential election. I responded to a public invitation by artist Tony Labat, working with SFMOMA, to perform a one-minute monolog on the theme of the Uncle Sam military recruitment poster: I Want You. We were to imagine for one minute we had the pointing finger and a voice of authority. I wrote:

I Want You to find Barack Obama in the face of every young black man.

I Want You to recognize intelligence, kindness, and concern about our society in the faces of all young black men.

Most of us have been trained to believe that just one color, whiteness, is synonymous with goodness.

We’ve been persuaded, silently, against our integrity, to make young black men,

like my son, and young black women, like Obama's daughters, invisible.

I Want You, I want us, to acknowledge that reality, un-train ourselves, open our hearts.

Reflecting on his own experience of racism, my 10-year-old child asked me to tell you this: “Think before you speak. And only speak positive words.”

I Want You to End Racism, thought by thought, word by word.

8.

Ferguson and Gaza. We rage, and tremble to describe this place we are in. “What comes after?” Nathan asks on his waterline.

9.

“What I have been thinking about lately is bewilderment as a way of entering the day as much as the work,” writes Fannie Howe in her book The Wedding Dress: Meditations on Word and Life. In the introduction, she describes raising her three biracial black children in Boston in the 1970s. She claims “bewilderment as a poetics and a politics,” an idea she developed “from living in the world and through testing it out in my poems. . . . For me,” she writes, “bewilderment is like a dream: one continually returning pause on a gyre.” She considers herself a spiral-walker: “there is no plain path, no up and down, no inside or outside,” she says, “ But there are strange returns and recognitions.”

10.

I’m sensing landmarks lining up with each other, so I’m better able to fix my position. And the wind is now at our backs. More clear-headed, I realize why not ask for directions! Nathan, I say, what’s your process? He replies: “For the donut rings, I cut out a flat circle with a hole in the middle and it begins by growing sides or walls that lean out with gravity as far as they can without falling. It’s a game really, balancing the weight of the clay and the force of gravity. . . . They are unreasonably thin for their form. A cone or cylinder can be made quickly—the form holds itself up. Making a pillow is slow and difficult—all that clay hovering out over an open space. When I am excited I often build too far up too fast and have to cut it off before it falls over. The white one nearly did fall over.”

11.

Risk is survival advantageous. Although humans love shelter, it’s seeking prospect and taking risks that exercise our survival skills. As I advance into unfamiliar territory, my mental map reshapes itself, and the “place cells” in my limbic brain fire rapidly in triangles. In that primitive part of my brain, layers of memory and emotion and past experiences of resetting myself are providing cellular orientation. In a minute I think we will see land.

12.

I’m handing over the language of arrival to Gertrude Stein. “I really do not know that anything has ever been more exciting than diagramming sentences. I suppose other things may be more exciting to others when they are at school but to me undoubtedly when I was at school the really completely exciting thing was diagramming sentences and that has ever been to me since the one thing that has been completely exciting and completely completing. I like the feeling the everlasting feeling of sentences as they diagram themselves. In that way one is completely possessing something and incidentally one’s self.”

13.

Navigating, rolling out and piling clay, making noise, risking voice. I propose in the full tide that’s flowing now that what we are searching for is not a paradise of certainty, not that forever-lost place, but rather a longed-for wave of place-making verbs tall with diagramming excitement and forward motion that will tumble us into something new. In late August, 23 years ago, the USSR collapsed suddenly. “The pace [of change there] in the third week of August,” wrote John Berger, “was no longer that of an historical process but of a sudden resurgence of nature. It resembled fire, wind, or desire.”

14. I open this last line of the sonnet to you: “Each of us is a navigator,” says Huth, in the book I quoted from at the beginning, The Lost Art of Finding Our Way. How are you making your way? How should we describe this place we are in? For certain, we have mental maps, diagramming energy, and beacons we can share. Would anyone like to toss something out into this arriving place between land and sea?

Kari Marboe, Five artists / Six sculptures, Harrison Street Studio, 2011

The Bouyant Bat

When they first met her cheeks flushed with blood from the initial burst of connection and engagement. They married. She went for a degree in accounting and he opened up a coffee shop across the street from her school. Upon graduating she kept the books and tended the counter. Upon graduating he told her she would keep the books and tend the counter. A few jokes and commonalities turned out to be the extent of their potential. She liked the structure of his life and he liked hers and they thought love would come. There was a feeling that it could be wonderful but they had no idea what variable to tweak.

So they set out to fix it. They purchased flowers chocolates neckties tickets puppies burial plots offspring and stored them all in the living room of their one bedroom apartment above the cafe. They waited to want them. Waited to feel something from them. And maybe they would spend a Sunday afternoon rearranging them and talking about it. Stack the flowers on the box of neckties, dear, and try the infant on top of the chocolates.

Year after year they stood, slept and spoke next to one another, together and abandoned. And that pang of attraction still hit her when she heard his voice next to hers in the morning. And that pang of interest still hit him when he saw her shadow on the floor in the evening. And sometimes when relating to the customers they hoped the other would hear and love would grow at last.

One afternoon there was storm and then a flood and the cafe filled with water. They had been living in parallel lines but now turned towards one another. She picked up a floatation device for them to hold onto and he grabbed a wooden bat to clear the architecture from their path. They combined their ideas only to watch their creation fail. The object didn’t float and it didn’t clear the way either. It was not a good fit and the weather continued to wash away what was once only barely there.

Micheal Swaine, Five artists / Six sculptures, Harrison Street Studio, 2011

“stage direction for 20 or more sticks {or how to build a fire}”

note to every one about props{taken from Wikipedia} {object 2}

“Many props are ordinary objects. However, a prop must "read well" from the house... meaning it must look real to the audience. Many real objects are poorly adapted to the task of looking like themselves to an audience, due to their size, durability, or color under bright lights, so some props are specially designed to look more like the actual item than the real object would look. In some cases, a prop is designed to behave differently than the real object would...”

the prop shop did a great job so that reality can be read well from the back of the audience

as the stage manager my goal is to get you ready for the day when we have an audience

you might be thinking

“I am not an actor”

yes, let me repeat that

you are not the actors!

but with out our skill of giving the actor the prop needed

at the correct time

the play would lose meaning or would completely change

if you accidently hand the actor who is running onto the stage

the gun instead of the cigarette

you can imagine how the scene will change in meaning

all good plays need ways for actors to relate

or relating starts with the hand revealing the meaning held by an object

we here in the theater business call them props

but these objects will control the action of the play

control the direction of meaning

If we put a cell phone on stage we know someone is going to start texting

our job is simple but important

put the objects in the correct order

the riggers have not hung the cables

so that these props for the final show will fly into and out of the scene on cables

but for now,

for this run threw I will just hold the object where it will land on stage

you should try to imagine that it will magically fly down from the up above and fly back into the rafters

all props have a number written on them

please write down the number with your notes

so our objects do not appear out of order

here we go:

ohh I almost forgot

can I have a volunteer just a stand in for the actor

you will not have to do anything except stand where the tape mark is

for the real play this will be an actor, who will be saying their lines

you will just stand there you do not need to recite the lines

again we are not actors

I just need a volunteer to stand right here

you in the back … the new guy... you are about the same height as the real actor(*SWAINE ASKS LYNCH TO BE THE ACTOR)

thanks great stand right here:

here we go again:

act one : scene one :

will start with a moment of relaxation {objects: 12, 4, 3, 20,7,13}

like when you are connected to a normal day

leaning against the wall of a building out on the streets

waiting for things to start

waiting for something important to happen

the curtain rises

act one : scene two:

objects that facilitate relations often come in a box

but sometimes you don’t have the neat box of 20

often I search on the ground and find a bent half used stick {object 5}

then the object is picked up and put in my mouth

the moment when we lite a cigarette waits

so the actor leans and waits

looks out in the crowd

that appears to be looking at him

then in his mind he starts to imagine {object 1}

someone beautiful coming to him

he sees it happen and then he imagines

what happens next

the positions they will get in {object 6 and 9}

he remembers the being connected to the wall

he notices he is starting to feel something in his gut

but he needs a match {object 17}

he needs the ability to light a fire

act two :scene one:

it is easier to bum a light then a cigarette

but getting a date is even harder

often I lean against this wall and smoke and wait for some one to come up to me and ask if I have a cigarette they can bum

but I never have one to give to them

or I don’t have one that is not bent or half used

so instead I ask them to do something else

and I get excited{object 14} imagining this scene

but then my head wonders and the picture changes

their are moments that someone else holds onto our excitement for us

I look down at them

Act two scene two

I start to think of that jack London story about making a fire

and I start to feel cold

and wish I had that match

and their are moments that our excitement lessons {object 16}

as reality grows darker and colder

that is a lesson

Act three: scene one:

then I feel get sick

it could be the cigarette I picked up off the ground

or what that guy did while I leaned against a wall in that back alley

I really feel sick

I don’t even have time to get to the bathroom

{look at the bathroom}

I am out here on the streets

we think about digging a hole

I do have a shovel{object 8}

but before I start to dig

ok. we will take a break and do the rest of the stage directions after the break...

Maria Porges Five artists / Six sculptures Harrison Street Studio, 2011

Stories for Nathan

1

Wherever we move her, we need six pillows. Two, to place beneath neck and knees; one each for arms, and the last ones to keep her from rolling away. That’s a joke, of course. Naomi could no more revolve her way to freedom than could the couch on which she lies most afternoons. Still, she’s stronger thanshe seems. I dreamed one night that she had risen-- not sat up—but, literally, floated to the ceiling in her supine position. Then she drifted out the open window, her long hair trailing below her like a mass of delicate roots released from the earth.

2

Frozen, papery bits of leaves make the only sound at that pre-dawn hour, crushed by our cautious booted feet as we walk the long road of frozen dirt. Too cold, almost, to breathe without a scarf to filter the air, and Charlie has only an old black cap, lumpy, worn. He pulls it around his lower face, stretching the knitted wool over everything except his eyes, which looks so damn ridiculous that Livia starts to laugh real loud and can’t leave off until she slips on the leaves and falls, pretty hard, on her skinny butt. We help her up. More mad than hurt, she curses our aunt for making us do this. Building character, the old bitch calls it. At night, I hear Gordy asking God for her to die, so we can be real orphans, and live somewhere there are other kids and a place to get warm.

Maria Porges

2011

Cooley Windsor, Five Artists/Six Sculptures, Harrison Studio, 2011

IT COULD BE YOU IN THIS JOURNAL

When I was younger I went to a lot of readings, but it wasn't because I wanted to be read to. It was because I wanted to write but did not know how. I did not know how to start. After a while I realized that there were a lot of people in the audience in the same situation. The author would read, and then during question-and-answer time someone in the audience would always hold up their hand and say that they were interested in writing, what should they do? and the the author would answer, "Write," and the audience would laugh.

Even then it was clear that being told "Write" is not helpful to someone who wants to write but does not know how to start, and being laughed at is not helpful. I wanted to ask the same thing, but because of what I had seen at so many readings I knew not to ask, but that is what I wanted to know.

So I have decided to start this piece answering the question, How can I start to write? And here is a way that you can get yourself started.

Albert Schweitzer concludes The Quest of the Historical Jesus with this paragraph:

"He comes to us as One unknown, without a name, as of old, by the lake side, He came to those men who knew Him not. He speaks to us the same word: “Follow thou me!” and sets us to the tasks which He has to fulfill for our time. He commands. And to those who obey Him, whether they be wise or simple, He will reveal Himself in the toils, the conflicts, the sufferings which they shall pass through in His fellowship, and, as an ineffable mystery, they shall learn in their own experience Who He is."

That is what we want to hold in mind: The divine is speaking to us in the language of our own experience. So what we want to do is write in that language, the language that life is speaking to us in, the language of our own experience. So what I have done for this piece is write down on nine note cards statements that I have heard in my life that are important to me as an artist. Each statement is from my own experience that guides what I do. Nine note cards, and the only thing that each one has on it is just the simple statement that is important to me.

So what you do is think of your own life, of the things that you have heard and that have been told to you that are most important to you, and just write the simple statement down on a note card. Don't make it fancy. Don't make it hard. Just write down the quote. Write down as close as you can what it is that life has told you.

Then when you have some cards, you are going to talk to yourself out loud and say briefly the context of how you came to know the statement that is on each card. Then later you will write down what you said.

So I have nine cards, nine statements from my own past, and I have written down the little story that accompanies each one. It was not hard to do. It was like writing a letter or an email to you, even though we don't know each other yet, and if you want to write, this is a process I recommend.

Card one. Here's what you need to know. I was working at Indiana University summer camp at Lake Brosius in 1983 and was assigned to paint a long wooden fence. I had never painted anything before, and so I stood beneath the broiling afternoon sun meticulously painting and painting this wood fence white. The enormous three-hundred pound high-school wrestling coach named Big Jim from Indianapolis who was my camp supervisor watched me struggle for a while, then bounded over and gently confided to me, "You are going too slow. Just slap it on. It ain't no church."

People, this is a major truth. Not everything worth doing is worth doing right. Big Jim's message, slap it on it ain't no church, has been one of the lights of my life. A lot has gotten done that would not have gotten done, and gotten done a lot faster, inspired by brooding on Big Jim's statement. Art is not surgery. You do not have to be that careful. You do not have to worry if you fail. It is like teaching yourself to whittle. If you cut the stick in two, you are pressing too hard on the knife. But if the stick isn't changing shape, you are not pushing hard enough. That is how you do it. You talk to the material and the material talks back. That is how you learn a craft like writing. It is like talking. If you worry too much about what you are going to do or how you are going to sound, you inhibit yourself, which is the opposite of what you need. So that is

what you need to think of when you are starting--just slap it on it ain't no church.

The second card is a variation on the theme. This one was told to me in third grade by my best friend Archie Castleberry's chain-smoking alcoholic grandmother who was in her 70s and had been married during Prohibition to a bootlegger. Archie and I were at his grandmother's house complaining about something not being how we wanted it, and his grandmother snapped, "Baby want a titty?" That shut us up and shocked me, and although I seldom say the statement out loud, I often think it. Oh, I need this, oh I need that, oh they won't let me do what I want to do, oh they are not being fair to me. It is true, they have not been fair to me, but then I just have to think of old Mrs. Castleberry and the titty and go on and do the best I can. I also often think of the statement when other people complain to me.

The third card was from my beloved friend Robert Castleberry's maternal grandmother, Mama Phylls (pronounced Files), who was a hard person who had lived a difficult life. Her daughter who was Robert's mother, Betty Jo, often abandoned the children, and Archie, Robert's brother, developed rickets as a child because he was not properly fed. Mama Phylls was very frugal, and one of her favorite things to say to children who were playing with something was, "Go ahead, just tear it up. It's paid for. Just tear it up." I can still hear that cruel disapproving voice. Part of it is now mine. I can hear it in myself. What we didn't understand is that it didn't make any difference. Every one of those people--Robert, Archie, Mama Phylls, Betty Jo--is dead now. The things are gone and so are the people. All that being careful, and nothing is left.

The next card is something my mother told me when I was a child. She had been orphaned when she was ten and passed around to relatives, none of whom wanted her, but even though I was in grade school I could tell this advice was absolutely right the moment she spoke it, and I vowed on the spot to adhere to it, and I have. What she said to me was, "When you grow up, always pay your rent on time. You can get a church to feed you, but you will need somewhere to stay at night."

The next card contains what the counselor Dorothy Foster told me when I asked her what professional meant. People were always talking about professionalism, but I had come to hate the word because it usually seemed to mean dressing up and being circumspect all the time. But Dorothy Foster told me that professionalism meant that the client's interest was always the principal concern, and that every action taken was taken because it was in the client's best interest. She told em that the person providing professional service could also enjoy it, but that the main benefit had to accrue to the client.

Then she told me about a time when she had been working with a client who thought he could astral project, and she set up several experiments so he could test it. He failed the experiments. He couldn't astral project. But Dorothy Foster said that later she realized that she had been wrong to do that, because it was based primarily on her own personal interest and not what was best for him at the time. She told me that over thirty years ago, and I still think of it and am guided by it, and it is the definition of professionalism that I love.

My mother used to mortify me every time I was bicycling away from home by standing on the porch and yelling, "Look out for cars because they won't watch out for you." That's something people in creative disciplines need to think about. David Mamet used to offer himself up as an example of the dictum that nobody with a happy childhood ever went into show business. Creative people are often sensitive. They feel things. They get hurt. And the offshoots of this can be at the ends of things, like liquor bottles and pill bottles. The names say it: Van Gogh, Plath, Rothko, Garland, Hemingway, Monroe, Joplin--and these were the successes.

The same qualities that can make us artists can make us drunks and depressives and self-destructors. I point this out to you as someone who knows something about it. I came from a tortured home, and I have not had an easy life, but here is a representation of me in front of you. I almost didn't make it. When I was twenty-three I poisoned myself with phenobarbital. My heart stopped, but fortunately an ER doctor at Parkland Hospital in Dallas pounded on my chest hard enough to fracture my sternum and get the heart beating again. The sternum grew back wrong and even now, almost forty years later, it hurts when the weather changes.

A lot of times in art we emphasize the parts of our lives that make us look good--I won this award, I went to that school on that fellowship, I published this here, I was invited to speak there--and the attempt, naturally enough, is to look golden. But people interested in working in the arts should bear in mind that is can be like working in the wood shop. Many of the tools have blades, and you need to keep your eyes open. You need to look out for cars because they won't won't look out for you.

My next-to-last card asks, "How was Jamaica?" I spent Christmas 1983 in Ocho Rios with my friend John Gleaton. I was estranged from my family at the time. One month later, my mother unexpectedly died of a heart attack. I went home for her funeral outside Tulsa. I was the only tan person. A number of my mother's friends said to me, "It's too bad you couldn't come home for your mother's last Christmas. How was Jamaica?" It was not meant friendly. I gave up and kept repeating, "Oh, it was lovely. I hope to go back someday."

As a person, as an artist, whatever you do, you will occasionally fail, and you may fail often. You will be embarrassed, mortified, guilty. Sometimes you will be hopelessly wrong. People will criticize you and what you have you done. Things will not turn out as you hoped. Now, decades later, when that happens to me, I secretly ask myself, "How was Jamaica?" and that calms me. Everyone needs to build a place inside themselves where they can go when they flop, and if you do not occasionally fail you should be working on a larger scale. It is survivable. How was Jamaica?

The last one is a great quote from a ceramics artist that I met from Rhode Island School of Design who was a friend of a friend. This woman told me about when she was maid of honor at Gabe and Catherine's wedding. Gabe's mother never liked Catherine, and for some reason Catherine was two hours late to her own wedding. While everyone at the ceremony was waiting for Catherine to show up, the groom's mother became furious and finally snarled to the maid of honor, "We have got to get started," and the maid of honor snapped back, "What do you want me to do, shit a bride?"

In art, that is exactly what you want to do. That is the purpose of this exercise with these note cards. What you want to do is write down simple statements that are important to you, that you recognize have taught you about life, and then write down their context so that other people can understand. The most important thing in writing is to have something to say. Once you have that, you are most of the way there, and writing it on cards is easy and fun.

So this week, make a date with yourself, and say, I am going to slap it on it ain't no church, work on your note cards and shit a bride. Writing is mainly talking to yourself, and really, how hard is that? The whole world is talking to you. Just write down what it is saying.

______________

--The quote is from The Quest of the Historical Jesus by Albert Schweitzer, translated by W. Montgomery, Dover Publications, page 401, 2005, an unabridged republication of the second English edition of the work originally published in 1911 by Adam and Charles Black, London.

Richard T. Walker (on cassette tape), Harrison Studio, 2011

Dear Listener,

Thank you for taking the time to listen to this recording.

Something very strange happened to me the other week. I suddenly could no longer bring myself to speak. I couldn’t talk.

I couldn’t quite assess whether this protest was political and that words had retreated purposefully, taking their agency with them in order to reduce my understanding of this world to a collage of memory, fantasy and illusion.

I wondered whether they had actually become ashamed and could no longer live with the knowledge that what they claim to be is only ever in relation to the thing to which they reference. Did their yearning to exist in reality as objects, as things, eventually just

become too much to bear? Did they retreat, truly ashamed by their inability to present things adequately estranging themselves form meaning because they had the wisdom to see that our relationship as it was, was ultimately unsustainable.

Without words I had to reconfigure how I thought about the world. The references from which I usually drew were becoming fainter and fainter, less and less familiar or indeed relevant. I realized that the majority of what I was trying to access was imagery and references brought about through the memory of photography and film and that it wasn’t really getting me anywhere because I didn’t own any of it. So I decided to think in terms of shapes, reflections, colours, shades, textures and even smells.

I tried to eradicate meaning from all forms. And it wasn’t fun. It was traumatic actually and I mourned for language and meaning so desperately. I had nothing to hold onto any more. All things collapsed and the space between my mind, my body and the outside amalgamated to form a large blob of nothing and everything. I panicked but panic had no voice. It was lost, groundless, static.

I lay on my back and looked up into what I remembered as the sky. Looking at the shapes in front of me I suddenly saw something glowing. It was reflecting but not quite. As if its intention was to reflect but it was failing, and that all it could really do was shine. And shine it did. It got closer and hovered above my head. I reached up and I touched it. Where I touched it seemed to change slightly, the area stopped shining. It was as if I was taking away its promise somehow, by placing my fingers upon it I had reduced it to something real, something there; a moment that had become. But the rest still shined, it was still to be.

I realized what this was. This object was essentially what my words were trying to be, what they desired to be; it was something and it was also a reference to that very same thing at the very same time. In fact it collapsed time. It was amazing. It was a living loop,

a paradox. But it was there, existing on its own terms in complete defiance of logic.

I stayed with the object all night and it just stayed there with me, floating. Eventually I had to leave but it would still be there when I returned. I would spend the next night with it, and I spent the one after that as well. We formed a bond, a companionship. There was

simplicity it its form that said everything I needed to hear. If questions arose in my mind then those questions would somehow turn into their own answers. The object had a power over me that was unfathomable.

But then it disappeared. It was gone. I was sad and troubled by it’s sudden absence. I had come to rely on it. It stood in for language. It was my words and became the vessel through which I understood everything. Initially I felt very lost. But I soon realized that this object had given me something. It had given me the ability to see again without the filter of words. There was a purity to things now, nothing was represented anymore; it just was.

I soon found that sounds came back to me. My mouth could make noises again and over time these noises became words and then sentences and then paragraphs. But whenever I spoke there was an echo, but it wasn’t a sound, it was an echo of that shape, that silver

egg-like structure that was so kind to me during those long lost nights. It was as if the shape and my words had made an agreement. The shape and the words had become the

same thing.

This was perfect, as the words had got exactly what they had desired. They were now signifier and signified. They existed as form.

So the chances are that as you hear this recording of my voice saying these words there is a large, silver shape a bit like half an egg, floating somewhere above this recorder and if you look closely you may even see the area that I touched on that first night, the area that no longer shines.

So be careful not to touch it, as that shine is very, very important. For it is through the shine that it can always, and will always be.

Sincerely.

Michael Swaine

engaging the audience